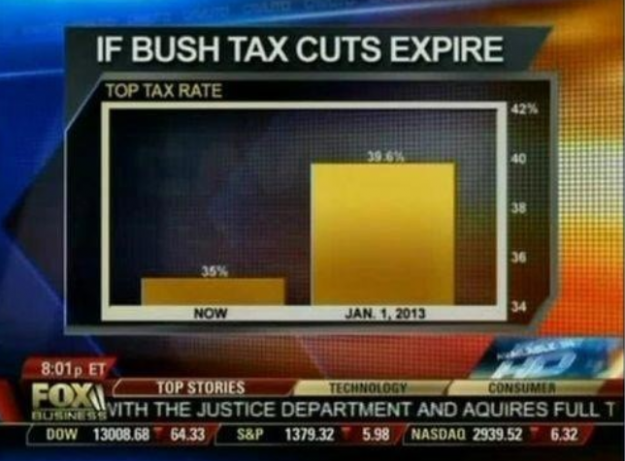

So a friend of mine posted this picture on their Facebook wall, and its message seemed well-intentioned but also so very problematic.

Let me first state that I do think that California must make hard decisions about water restrictions and water use, and I don't think that the current forms of water restrictions and bans are anywhere approaching what would be an equitable diminution in water use (and never mind the problems that California's system of water laws, interstate compacts, and inter-watershed irrigation systems play in creating further problems in the legal, political, and water management worlds). However, I don't know whether this image presents a useful comparison on all fronts. Furthermore, the presentation is arguably deceptive, since the compared units are not the same, with toilets (presumably being the one thing that the viewer is supposed to be sympathetic toward, since it is placed last) being based on a very low metric of

gallons/flush of one toilet, and all the rest (presumably the ones the viewer is supposed to feel antagonistically toward, since they are often held up as being "enemies" of water use) being based on really large

sector-wide annual figures.

This simplistic switch of metrics undermines the presumed argument of the image on two fronts. First is the casual deception: why present sector-wide annual figures for the "bad" water uses, and personal, single-use figures for the "good" water use? This presentation does not present an easy-to-grasp comparison between water uses at the State level. (There is also the problem of using words like "million" and "trillion" to describe the amount of water used, since it is so easy for people to lose the differential scales between hundred, thousand, million, billion, and trillion, but those sorts of distinctions are better covered in places such as this visualization of what

$1 trillion looks like.) In order to place the water used in Californian toilets in direct comparison with the others, we must first convert the value of 1.6 gallons/flush into a figure of gallons/year throughout California. When we do this, we find that toilet-flush water use in California is

at least:

1.6 gallons/flush (

x 5 flushes/person/day)

= 8 gallons/person/day (x

38,800,000 Californians)

= 310,400,000 gallons/day in California (x 365 days/year)

= 113,296,000,000 gallons/year

(I write "at least" 113,296,000,000 gallons/year, since I am using the figures for household toilets and only 5 flushes/day, even though the average is somewhat higher. This number doesn't include, of course, water use statistics for public toilets, urinals, port-a-jons, etc.)

Now let's list all the water uses presented in the picture in increasing gallons/year:

70,000,000 gallons/year (fracking)

400,000,000 gallons/year (Nestlé bottled water)

113,296,000,000 gallons/year (toilet flushes)

1,100,000,000,000 gallons/year (almond farms)

When we look at toilet flushes in this perspective, it is clear that it

is 1,618 times greater than the reported value for fracking. Furthermore, it is

283 times greater than the reported value for Nestlé bottled water. Indeed, when presented in this way, California toilet-water use can be presented as being far more profligate than either fracking or Nestlé bottled water, and by a LONG shot, simply because California has SO many people, and almost 60% of that population (

22,680,000 in 2010) lives in sunny, drought-ridden SoCal. This places domestic water use (which includes baths/showers, toilets, dishwashing, lawn irrigation, carwashing, etc) far ahead of most industrial water uses... save agriculture

Indeed, when compared to the reported value of almond farms, toilet-water use is a

mere 10%. However, there's a problem with the number presented in the graphic for almond farms. Specifically, the number of 1.1 trillion gallons/year is 1.6 times greater than

the value reported by Hanson out of UCDavis, whose figure of roughly 2.1 milion AF/year works out to roughly 680 billion gallons/year (compared to this number, toilet flush water use is roughly 16%).

Let's look, though, at water used to grow alfalfa, which is, according to Hanson, the largest agricultural water use in the State. Accordling to Hanson, alfalfa grown in California uses roughly 5.2 million AF/year, or roughly 1.7 trillion gallons/year (which is about 2.5 times greater than the amount he reports for almond and pistachio irrigation). The second-largest agricultural water use (reported by Hansen) is for forages, which uses roughly 3.3 million AF/year, or roughly 1.1 trillion gallons/year.

So we can see that -- from an argument based around comparative water uses alone -- the merits of placing fracking and Nestlé bottled water fall flat, since toilet-flush water use

far outstrips both of these two uses

combined. It would have been a better argument to put up alfalfa farms and forage farms. However, it's almond growers that have been in the news, and not alfalfa or forage, which is likely why it is almond growers that are shown (even though they are not the largest agricultural water users, and even though they have a far more valuable crop than either alfalfa or forage crop farms).

Now, one could still use the water use figures presented in the graphic to make associated arguments, but I was unable to find a single argument that held true against the fracking, Nestlé, and almond farms while preserving toilet flushing. For example, one argument for water conservation that is often made against fracking regards removing water from the hydrological cycle completely, and it's true that one could make the argument that water used in fracking is effectively "lost" to the immediate hydrological cycle (since fracking wastewater is often deepwell injected) and therefore cannot be used for drinking or any other use, but that argument doesn't hold for almond farming or bottled water, since both return their water to the immediate hydrological cycle (primarily as groundwater recharge, evapotranspiration, and biomass decay in the case of almond farms and as urine that is flushed down a toilet in the case of bottled water). So the argument that it's about removing water from the hydrological cycle use is not valid across cases.

Another common argument against fracking, irrigation, and bottled water is that these uses are

consumptive uses. In the case of fracking, this is undoubtedly true (as laid out above), and water used in agriculture is often also considered to be consumptive. However, the charge of consumptive use can also leveled at most of California's toilet water flushes, since much of the State's water is

pumped from watersheds in Northern California and the Colorado River, creating consumptive water use pressures in those areas.

The only real argument that comes to mind is that it is unfair for the government to impose water restrictions upon flesh-and-blood citizens but not impose water restrictions upon corporate "citizens." However, such an argument isn't a

water volume argument, but a

water rights argument, especially in how Californian water rights are not egalitarian, with a large part of this argument lying in the problems associated with California's water rights laws. Most individual Californian citizens do not own any water rights, let alone water rights that predate 1914. The date of 1914 forms the demarcation date between so-called "junior" and "senior" water rights, and those holding junior water rights will have their rights to water curtailed before those of senior water rights holders. Such a system of rights is based on a "first in place, first in right" principle, with a strong incentive for the right to be held by a non-human entity (such as a corporation, water district, or the like), since the death of an individual could lead to the "death" of that right. From an equity perspective, such distributions of water rights is inherently inequitable, since it creates structural inequalities that become evermore entrenched as the value of water increases (making the purchase or transfer of water rights less likely to occur). During times when water availability is high, such a structurally unequal distribution of water rarely impacts large swathes of citizens. In cases of drought, though, such inequalities emerge. But regardless of the structural inequalities that California's water rights system imposes upon its citizens, the percecption of unfairness in who gets the restrictions is not due to water volumes (as the graphic implies), but due to water policy and water law.

One "good" note though (if only from a perspective of masochistic

schadenfreude), is that if the drought continues, it is likely that even those holding senior rights (which includes many major agricultural water users)

will have their water withdrawals restricted.

In sum, while bottled water and fracking are often seen as problematic for various social, public health, and environmental reasons, the comparative water consumption in these two sectors doesn't hold a candle to the total sector-wide water consumption of toilets. Furthermore, hiding the scales of water use between different water uses in the way presented in the graphic is deceptive, and such deception can foster mistrust of the messenger or supporter of the message. In other words, in order to make the graphic less deceptive and more salient to a message associated with different types of water use, it needs more than just a simple comparison of water volumes.

Of course, this additional nuance can create problems when trying to disseminate a message...